Context engineering is the key to unlocking reliable AI agents or AI assistants.

Prompt engineering involves crafting a single instruction. Context engineering is the system-level discipline. It involves architecting the entire information pipeline an AI sees. This includes instructions, memory, retrieved documents, and tools.

This guide provides actionable context engineering examples covering definitions and approaches by OpenAI, Anthropic and LangChain. It moves you from basic prompts to building sophisticated context engineering for AI agents. These agents are designed to get the job done right the first time.

I will be covering context engineering in more detail, subscribe to get updates:

Key Takeaways:

- It’s a System, Not a String: The most common misconception is confusing context engineering with advanced prompt engineering. Prompt engineering is a subset of context engineering, focusing on the instructions. Context engineering is the complete system responsible for managing everything the Large Language Model (LLM) ‘sees’ within its context window. This includes not just the instructions but also dynamic components like memory, retrieved files (RAG), and available tools.

- Context Has 4 Pillars: Effective AI agents are built on a foundation of four distinct types of context. A robust context pipeline assembles information from:

- Instructions: the static system prompt

- Knowledge: dynamic information retrieved via RAG

- Memory: conversation history and user preferences

- Tools: API definitions the agent can use

- Strategies Manage Context: An agent’s context window is a finite and valuable resource. As a conversation continues, this window fills up, which can lead to performance degradation or failure. Professional context engineering requires active management, using strategies like compaction (summarizing history), compression, and trimming (dropping old messages). This keeps the AI focused on the most relevant information.

What is context engineering (and why is it not just fancy ‘Prompt Engineering’)?

I have already explained what is prompt engineering with best practices across multiple prompt engineering types below and use cases below:

- Learn what is self-consistency prompting

- Learn markdown prompting for AI best practices

- Learn multi-modal chain of thought prompting technique

- Learn prompt chaining method

- Learn tree of thoughts prompting technique

- Learn how to use ChatGPT for content marketing

Also, learn more by joining 20 communities to learn prompt engineering

To recap,

Prompt engineering is the skill of telling an AI exactly what you want with clarity and the right context. This helps AI respond usefully and consistently. You choose the words, examples, and format to steer the model toward the outcome you need.

Let’s introduce the core concept of context engineering by contrasting it with prompt engineering, using a concrete failure-to-success example.

The ‘Agent Sasha’ example: When good prompts meet bad context

Let’s imagine ‘Agent Sasha,’ an AI shopping assistant for a large e-commerce site. A user, who has interacted with this bot before, sends a simple, natural-language prompt.

User Prompt: “Hey, I need a new jacket for that trip I’m taking.”

Failure 1 (Wrong Context: Memory)

Agent Sasha’s Response: “Great! Here is a heavy-duty arctic parka with 800-fill down, on sale for $499. It’s our top-rated jacket for extreme cold.”

The user, understandably, is confused: “What? I’m going to the beach!”

Why this is a Context Failure, not a Prompt Failure:

You could argue the user’s prompt was bad because it was vague. But the user said “that trip,” which implies a shared history that a good agent should have. The failure here is a lack of context from two of our pillars:

- Missing Pillar 1: Memory (Short and Long-Term). A well-engineered system would offer Agent Sasha with long-term memory (e.g., a summary of past purchases, like the swimsuits and sunscreen the user bought last month). It would also give short-term memory from the current session. Or a recent one, where the user might have mentioned ‘my trip to Hawaii.’ The agent was blind to this history.

- Missing Pillar 2: Tools. A more sophisticated agent would have tools to resolve the ambiguity. It could have been given a

check_user_calendar()orget_upcoming_travel_bookings()tool. The agent’s system neglected to give it with the right tools to find the answer.

Failure 2 (Wrong Context: Knowledge and Tools)

The user clarifies, and this is where the second, more subtle failure happens.

User’s Follow-up Prompt: “Okay, I need a lightweight jacket for Hawaii, just for the cool evenings. And I’m allergic to wool.”

Agent Sasha’s Response: “Understood! This 100% Merino wool lightweight hoodie has excellent reviews and is perfect for a breezy beach evening. Would you like to buy it?”

Why this is a Critical Context Failure:

This failure is even worse. The agent “heard” the user’s constraints (they were in the immediate prompt) but was fundamentally incapable of using them.

Missing Pillar 4: Tools (Poorly Engineered). The agent’s search_products(query) tool was too basic. A context-engineered agent has tools that accept structured filters. The system around the agent has a critical role. It translates the user’s natural language constraint (‘I’m allergic to wool’) into a structured API call for the tool. An example is: search_products(query='light jacket', filters={'material_exclude': ['wool', 'merino']}).

Missing Pillar 3: Knowledge (RAG). A properly engineered agent would use Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) to know things about the user. It should have retrieved a persistent user_profile.json file that lists { "allergies": ["wool", "down"], "preferences": ["natural-fabrics"] }. This profile is static knowledge that should always be part of the agent’s context.

These two failures create the perfect thesis for our article. The prompt (the user’s instruction) was simple. But, the context (the entire system of information the agent needed to succeed) was missing. This brings us to a clear definition from our analysis:

Prompt engineering—that’s the craft of wording the instruction itself. And context engineering is the model-level discipline of providing the model with what it needs to plausibly achieve the task.

Here’s a brilliant diagram by Anthropic that summarizes the difference:

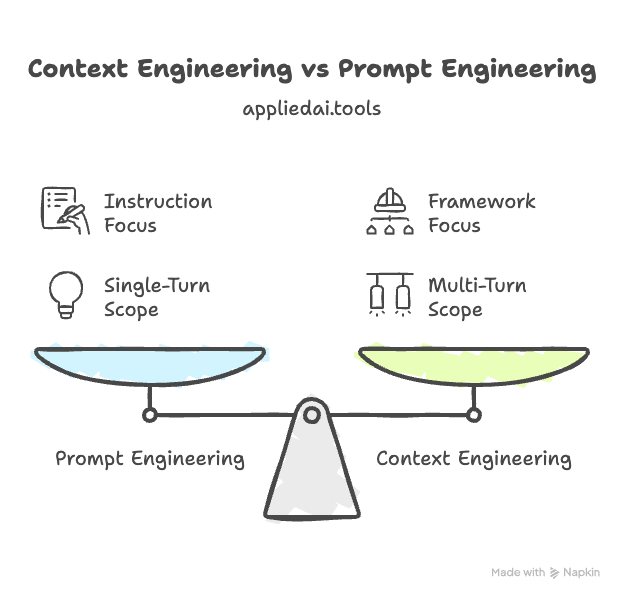

Context Engineering vs. Prompt Engineering: A Simple Breakdown

Many people new to the field confuse prompt engineering with ‘blind prompting’—simply asking an LLM a short question. While true prompt engineering is more rigorous, its focus remains on crafting the instruction.

Context engineering is the broader, next-generation discipline. It re-frames the problem: the focus is not on the string but on the framework that assembles the final context. Building effective AI agents has ‘less to do with the complexity of the code’ and ‘everything is about the quality of the context’.

The ‘magic’ of a powerful agent is simply high-quality, well-managed context.

The shift from simple chatbots to complex, multi-step AI agents is precisely why context engineering has become such a critical field. A single-turn chatbot only needs a good prompt. An agent, yet, must keep state, access memory, and use tools over a long-running interaction. These are all context engineering problems. As such, most agent failures are, at their root, context failures.

Here is a simple breakdown:

| Feature | Prompt Engineering | Context Engineering |

| Scope | A single instruction or query. | The entire information ecosystem. |

| Analogy | A question. | A full briefing packet + toolkit. |

| Goal | Get one good response. | Allow a reliable, multi-step task. |

| Example Components | Instructions, few-shot examples. | Instructions, RAG, Memory, Tools, State. |

The 4 Pillars of Context: An AI Agent’s ‘Working Memory’

Before an LLM generates a response, it is fed a large block of text—everything it can ‘see’ at that moment. This is the ‘context window.’ This window is often described as the LLM’s ‘RAM’ or ‘working memory’.

Context engineering is the discipline of architecting the dynamic assembly of the four pillars that fill this window:

Pillar 1: Instructions (The System Prompt)

This is the most foundational part of the context, often called the ‘system prompt.’ It is the static, high-level set of instructions that defines the AI’s core purpose, its persona or role (e.g., ‘You are a helpful travel agent’), immutable rules to follow, and the desired structure for its output.

For this pillar, an actionable tip is to follow guidance from AI labs like Anthropic. They recommend using ‘extremely clear’ and ‘simple, direct language’. It is also a best practice to structure the prompt using delimiters like XML tags (e.g., <instructions>...</instructions>) or Markdown headers (### Rules). This helps the model differentiate its core instructions from the other (dynamic) pillars of context.

Here’s a useful infographic highlighting the calibration of system prompt

Pillar 2: Knowledge (Retrieval-Augmented Generation, or RAG)

This pillar solves the problem of an LLM’s static, outdated knowledge.

RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) is the primary technique for injecting fresh, external, and private knowledge into the context.

RAG is a system that, in real-time, retrieves relevant snippets of information. It draws from an external knowledge base, like a vector database, company PDFs, or API documentation. It augments the context by inserting these snippets for the LLM to read.

In the “Agent Sasha” example, RAG is the system that would have automatically fetched the user_profile.json file. It included the wool allergy information. The system used that knowledge to inform the agent’s actions in two ways. Either it filtered the search results directly or it added a constraint to its internal reasoning.

Pillar 3: Memory (Short-Term and Long-Term)

This pillar provides statefulness and personalization.

- Short-Term Memory: This is simply the conversation history. It allows the AI to hold a coherent, multi-turn dialogue, referencing what was said just moments ago. It is also the primary part that consumes context window space.

- Long-Term Memory: This provides persistence across sessions. Typically stored in a vector database, this memory includes user preferences, learned facts, or summaries of past interactions. For Agent Sasha, long-term memory would be remembering the user’s past purchases (like swimsuits) or stated preferences from months ago.

Pillar 4: Tools (Giving Your AI ‘Hands and Eyes’)

This pillar gives the AI agent capabilities. LLMs, by themselves, are text-in, text-out systems; they ‘can’t check real databases or call APIs or execute code’.

Tools bridge this gap. A ‘tool’ in this context is simply an API or function definition (e.g., a Python function’s docstring and parameters) that is inserted into the context.

The LLM is trained to:

- Read the user’s request

- Look at the list of available tools

- Select the correct one

- Generate the JSON object needed to call it

For Agent Sasha, the context should have contained tool definitions for get_upcoming_travel_bookings() and a structured search_products(query, filters) tool.

Note: A critical tip for developers is to avoid ‘bloated tool sets’ with ambiguous or overlapping functionality. This can cause ‘Context Confusion,’ a state where the model is overwhelmed by choice. Performance can degrade significantly when an agent has more than ~30 tools to select from.

Actionable Context Engineering Examples: From Beginner to Agent

This is how you can start applying these concepts today, moving from simple techniques to advanced, agentic architectures.

Beginner: Prompt Engineering Techniques

The principles of context engineering can be applied instantly, even without building a complex system. These foundational techniques are about manually curating the context within a single prompt:

Role Assignment:

Start a prompt with a clear role, like, ‘You are a senior Python developer reviewing code for security vulnerabilities.’ This approach is a form of context engineering. It sets the AI’s contextual persona, which dramatically shapes its skill, vocabulary, and focus.

Few-Shot Examples:

This means ‘show, don’t just tell. If you need a specific JSON output, give 2-3 examples of input/output pairs in the prompt. This is the most effective way to give formatting context.

Learn more about few-shot prompt engineering along with examples:

Chain of Thought (CoT):

Adding the simple phrase ‘let’s think step by step’ to the end of a prompt forces the model to use the provided context to create a logical reasoning process before giving its final answer.

I have shared a detailed guide to chain of thought prompting here:

Agent-Level: How the Pros Manage Context

The true challenge of context engineering for agents emerges in multi-step tasks. The context window is finite, and as a long conversation adds memory and tool outputs, the agent’s ‘working memory’ fills up. This leads to ‘context failure,’ where the agent forgets its original goal or critical past information.

The solution is not just buying a larger context window; it is smarter management. This introduces a core engineering trade-off: Memory vs. Fidelity.

Trimming (or “truncation”)

Involves simply deleting the oldest messages from the context window. This is fast, cheap, and maintains perfect fidelity for recent events. Its major con is ‘abruptly forgets,’ leading to user-facing ‘amnesia’.

Summarization

Summarization is also called ‘compaction’ by Anthropic or ‘compression’ by LangChain)

Involves using an LLM to compress the older parts of the conversation into a shorter summary. This provides excellent long-term memory. But it is slow and costs an extra API call. It also risks ‘summarization loss’ or ‘compounding errors’ if the summary is bad or misinterprets a key fact.

A developer must choose their strategy based on the agent’s needs.

Here’s how the top AI labs implement these strategies.

Example 1: Context Engineering by Anthropic

Anthropic’s engineering guides highlight two key techniques for long-horizon tasks:

Compaction

This is their term for summarization. When a conversation nears the context limit, the agent passes its own history to the model with a prompt to ‘summarize and compress the most critical details,’ like architectural decisions or unresolved bugs. It then starts a new, clean context window with only this summary, freeing up tokens.

Structured Note-Taking (Agentic Memory)

This approach gives the agent a ‘scratchpad’ tool. In a famous example of an agent playing Pokémon, the agent writes notes to an external file, like “for the last 1,234 steps I’ve been training…” When its context is reset, it uses a tool to read the file, instantly regaining its goal and memory.

Example 2: Context Engineering by LangChain

The popular LangChain framework, especially with the LangGraph library, is built around a four-part strategy for context engineering. Here’s an elaboration of the infographic shared above:

- Write: Save information outside the context window (e.g., to a database).

- Select: Use RAG to pull only the most relevant memories or tools into the context for the current step.

- Compress: Periodically summarize the message history.

- Isolate: Instead of one ‘super agent’ with a massive, messy context, this architecture uses a “supervisor” agent. The supervisor passes specific tasks to specialized sub-agents (e.g., a ‘research agent’ or a ‘coding agent’), each of which operates with its own clean, focused context window. This separation of concerns is a powerful context management pattern.

Example 3: Context Engineering by OpenAI

The OpenAI Agents SDK automates memory management through a Session object. It directly exposes the core trade-off to the developer, forcing them to choose a strategy:

- Trimming: The session automatically keeps only the last $N$ user turns. This is described as ‘simple’ and ‘zero added latency’ but comes with ‘amnesia’.

- Summarization: The session automatically compresses older messages into a summary. This ‘retains long-range memory’ but adds latency and risks ‘compounding errors’ if a bad fact enters the summary.

The Future: Context Engineering is for AI Agents

The future of practical AI is agentic, and therefore, the future of AI development is context engineering.

The prompt is merely the ‘spark,’ while the engineered context is the “engine” that enables reliable and complex task completion. As leading AI researcher Andrej Karpathy notes, the goal is to fill the context window with “just the right information for the next step”.

I will be covering more about using context engineering for AI agents, subscribe to get updates:

Context Engineering Anthropic vs OpenAI vs LangChain: Approach Comparison

Here is a comparison table that breaks down their distinct approaches based on their documentation and official guides.

| Approach | Anthropic | OpenAI | LangChain |

| Core Philosophy | Find the “smallest possible set of high-signal tokens” that maximize the likelihood of a desired outcome. Context engineering is seen as the ‘natural progression of prompt engineering’. | Manage a finite context window to keep coherence, improve tool-call accuracy, and reduce latency/cost. The focus is on automating memory management for a single agent session. | Defines as ‘The delicate art and science of filling the context window with just the right information for the next step’. The LLM is viewed as a CPU and its context window as the RAM that must be actively managed. |

| Primary Focus / Key Abstraction | Techniques for enabling agents to perform long-horizon tasks (e.g., complex coding, multi-hour game-playing) that span multiple context windows. | Automated session memory management. The developer chooses a pre-built strategy (Trimming or Summarization) for the Session object in the Agents SDK. | A flexible, low-level orchestration framework (LangGraph) built on a 4-part “Write, Select, Compress, Isolate” strategy. It gives the developer granular control. |

| Memory Management Strategies | 1. Compaction: Using the LLM to summarize long conversation histories into a shorter summary, which then starts a new, clean context. 2. Structured Note-taking: An ‘agentic memory’ technique where the agent is given a ‘scratchpad’ tool to write and read notes, persisting its memory outside the context window. | Developer must choose one strategy: 1. Context Trimming: Keeps only the last $N$ user turns. It’s fast and simple but causes “amnesia” as it abruptly forgets long-range context. 2. Context Summarization: Compresses messages older than $N$ turns. It retains long-range memory but adds latency and risks ‘compounding errors’ (context poisoning). | 1. Write: Checkpointing agent state or saving to long-term memory. 2. Select: Using RAG to retrieve only the most relevant memories for the current step. 3. Compress: Allowing the developer to implement custom logic to periodically summarize or trim the message history. |

| Tool Management Strategy | Recommends curating a minimal, viable set of tools with clear, unambiguous descriptions. Explicitly warns against ‘bloated tool sets’ that cause ‘Context Confusion’. | Focuses on clear instructions and separators (like """) to divide static instructions (including tool definitions) from dynamic context. | Select (RAG for Tools): Provides a ‘Select’ strategy, often using semantic search, to choose only the most relevant tools from a large library for a specific task, rather than putting all tools in the context. |

| Key Architectural Strategy | Sub-agent Architectures: Using specialized sub-agents that operate with their own clean, focused context. These sub-agents then report condensed summaries back to a main coordinating agent. | The provided documentation focuses primarily on managing a single agent’s session memory. | Isolate (Multi-agent): LangGraph is explicitly designed to support multi-agent architectures (e.g., supervisor/swarm models). This ‘Isolate’ strategy allows context for sub-tasks to be managed independently. |

How to Start Learning Context Engineering?

The best way to learn is by building. You can follow a simple, three-step path:

- Step 1: Audit Your Prompt. Look at any current prompts. Find and separate the instruction (Pillar 1) from the context (Pillars 2, 3, 4). Use delimiters like

"""or<context>to create clear, structural separation for the model. - Step 2: Master advanced prompting techniques first. Practice Role Assignment, Few-Shot examples, and Chain of Thought.

- Step 3: Build a simple RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) application. This teaches the “Knowledge” pillar and is the foundation for most non-trivial agents.

- Step 4: Build a simple agent using a framework like

LangChainor theOpenAIAgents SDK. This is where you will learn the ‘Memory’ and ‘Tool’ pillars firsthand.

Many platforms now offer a context engineering course and several community guides serve as a context engineering book. But the best way to start is by applying the principles in your daily usage.

This brings us to the final, most important takeaway:

Prompt engineering… it gives you better questions. Context engineering—that gives you better systems when you combine them properly.

Frequently Asked Questions on Context Engineering (FAQs)

What is ‘Context Poisoning’ and how do you prevent it?

Context Poisoning is when incorrect or biased information gets into an agent’s memory and corrupts its future reasoning.

For example, if an agent’s summary of a chat includes a factual error, that error will be treated as truth in all future steps. You can prevent it with techniques. These include Context Validation (checking info before saving it). Another is Context Quarantine (starting a fresh context thread if poisoning is suspected).

What is ‘Agentic Context Engineering (ACE)’?

ACE is an advanced framework, proposed in a research paper: Agentic Context Engineering: Evolving Contexts for Self-Improving Language Models. It allows an agent to learn from experience by evolving its own context. It uses a three-part cycle (Generator, Reflector, Curator) to analyze its own successes and failures. Then, it curates those lessons into a ‘knowledge playbook’ (an advanced system prompt) to use on future tasks. This entire process happens without retraining the model’s weights.

What is ‘Vibe Coding’ and how does it relate to context engineering?

‘Vibe Coding’ is a term for programming with an AI where the developer guides the AI using natural language and high-level direction, rather than writing every line of code. Context engineering is the discipline that makes ‘vibe coding’ work reliably. A production-ready AI coding assistant isn’t just ‘vibing.’ It is a context-engineered system. It has the entire codebase, dependency graphs, and style guides available as context.

You mentioned ‘compaction.’ How is that different from just ‘trimming’ the oldest messages?

Trimming (deleting old messages) is fast but causes ‘amnesia. Compaction (or summarization) is an active process where the agent itself is used to summarize the conversation history just before the context window is full. This summary (e.g., “User decided on the blue jacket, file payment.json is pending”) is then placed at the start of the new, clean context. This preserves key decisions without the token overhead.

What is ‘Structured Note-Taking’ for an AI agent?

This is an advanced memory technique championed by Anthropic. The agent is given a tool, like a “scratchpad” or the ability to write to a file (e.g., todo.md). As it works, it writes down its goals, key findings, or a to-do list. If its context is reset (e.g., in a long task), its first action is to use its tool to read the notes file, instantly regaining its memory and goal.

How do I debug a ‘context failure’?

You can’t debug what you can’t see. The key is observability. Use a tool like LangSmith to trace the exact context (all 4 pillars) that was sent to the LLM for each step. Often, you’ll find the error isn’t the LLM’s logic, but that the RAG system pulled the wrong document, or the memory summarization dropped a key detail.

A practical tip: leave failed tool-call attempts in the context; hiding errors prevents the model from learning from its mistakes.

What are context engineering tools?

These are frameworks and libraries that help you build and manage context. The most popular context engineering tools are frameworks like LangChain 6 and LangGraph, or SDKs like the OpenAI Agents SDK.

Is context engineering LangChain a good place to start?

Yes. LangChain is a powerful framework that provides many built-in components for managing memory, RAG, and tools, making it a popular choice for building agents.

What is Anthropic’s context engineering approach?

Context engineering Anthropic’s approach focuses on techniques for long-horizon tasks. Their key strategies are compaction (summarizing long chats) and structured note-taking (letting the agent write to an external “scratchpad”).

What is OpenAI’s approach to Context engineering?

Context engineering OpenAI’s new Agents SDK focuses on ‘session memory. It gives developers a choice between trimming (keeping the last N messages) or summarization (compressing old messages) to manage the context window.

What is a context window?

It’s the AI model’s ‘short-term attention’. It’s the maximum number of tokens (words/pieces of words) the model can ‘see’ at one time. Context engineering is the art of fitting the most useful information into this limited space.

What is RAG?

RAG stands for Retrieval-Augmented Generation. It’s the core knowledge pillar of context engineering. It’s a system that retrieves relevant facts from your private documents (like a PDF or database) and augments the context with them.

What are common context failures?

Common failures include:

- Context Poisoning: bad info gets into memory)

- Context Distraction: too much history confuses the AI

- Context Confusion: too many tools make the AI unsure which one to use

How does context engineering AI work?

Context engineering AI works by running a system before the AI model is called. This system gathers all the necessary information—the instructions, the relevant chat history, facts from a database (RAG), and available tools—and assembles them into a single, perfectly formatted block of text (the “context”) for the AI to read.

Does context engineering work for multimodal models (vision, audio)?

Yes, the principles are the same, but the context is more complex. Context engineering for a multimodal model involves optimizing all inputs, like text instructions, image examples, and audio clips [],. For example, a system prompt might be paired with five “few-shot” images that show the desired style of visual analysis.

What is the ‘lost in the middle’ problem?

This is a known weakness of LLMs with long context windows. They tend to pay most attention to information at the very beginning (the system prompt) and the very end (the user’s last message) of the context. Information that is “lost in the middle” (like an important detail from 20 messages ago) is often ignored or forgotten. Context engineering strategies, like “Structured Note-Taking” or summarizing history , are designed to combat this by re-surfacing old, important facts and moving them to the end of the context.

What is ‘Outside-Diff Impact Slicing’?

This is a specific context engineering technique for AI-powered code reviews. Instead of just giving the AI the diff (the changed lines), the system automatically provides context from outside the diff. It “slices” and finds the callers (code that calls the changed function) and callees (functions that the changed code calls). This gives the AI the necessary context to spot critical bugs at the boundaries of the change, which are invisible in the diff alone.

Is context engineering just a temporary trend before models get better?

This is a common debate. Some argue that as context windows grow (e.g., 1M+ tokens), these complex management techniques will become obsolete. But, the prevailing view is that context engineering is the core of building reliable systems. Even with a 1M token window, ‘garbage in, garbage out’ still applies. The skill is in filling that window with high-signal, relevant information and filtering out nois. It is a discipline that becomes more important, not less, as context size increases.

Leave a Reply