Language models hallucinate because their training and evaluation techniques reward them for making confident guesses. They are not incentivized to admit when they don’t know an answer.

The discourse surrounding Artificial Intelligence is often dominated by the challenge of “hallucinations”. It is a term used to describe instances where a language model confidently generates plausible yet incorrect statements. Hallucinations undermines trust and remains a significant barrier to the deployment of AI in high-stakes applications.

A recent OpenAI paper argues that this isn’t a mysterious glitch. Instead, it is a predictable outcome of statistical pressures. Test-like scoring systems also penalize uncertainty.

You can read the AI research paper from OpenAI, “Why Language Models Hallucinate“.

The paper posits a comprehensive, two-part thesis:

- The potential for error originates from natural statistical pressures during the pre-training phase.

- These errors are persistently reinforced and amplified during post-training. This happens because the ecosystem of evaluation overwhelmingly rewards confident guessing. It values this over the honest admission of uncertainty.

This shift in perspective is the paper’s critical contribution. It moves the conversation from a narrow technical problem to a broader socio-technical one. This broader implication affects the entire AI development and benchmarking community.

3 Key Takeaways

- Hallucinations start in pre-training: For a model, learning language involves distinguishing valid statements from invalid ones. When data on a topic is scarce, the model is under statistical pressure. It makes its best guess in such cases. This guesswork leads to errors. These errors become the seeds of hallucinations.

- Evaluation makes it worse: Current benchmarks for AI models often use a simple right-or-wrong (0-1) scoring system. This motivates models to always give an answer, even a fabricated one. Saying “I don’t know” guarantees zero points. A guess might be correct.

- A socio-technical solution: OpenAI proposes a shift in how we evaluate AI. They suggest modifying major industry benchmarks to reward models for expressing uncertainty instead of creating more hallucination-specific tests. This change could steer the entire field toward building more trustworthy AI.

The problem statement with AI hallucinations

In the context of Large Language Models (LLMs), a hallucination is not a perceptual error akin to the human experience. It is a specific failure mode: the generation of a plausible falsehood with an air of confidence.

The paper makes this abstract problem concrete with compelling real-world examples.

When a cutting-edge model was queried for the dissertation title of Adam Tauman Kalai, one of the paper’s authors, it confidently produced three distinct, incorrect titles on separate occasions.

Asked for his birthday, it again invented three different wrong dates.

These examples are not mere trivia. They illustrate a fundamental challenge that persists even in the most advanced systems. This challenge erodes their utility and reliability. The model is not being deceptive; it is simply executing the strategy its training has taught it is optimal.

Debunking common myths about AI hallucinations

The paper’s framework serves as a powerful corrective to several pervasive myths that have clouded the discussion around hallucinations.

| Common Myth | The Paper’s Finding |

| Hallucinations are a mysterious bug or glitch. | They are a predictable and understandable outcome of statistical pressures during pre-training and misaligned evaluation incentives during post-training. |

| Bigger models and more data will eliminate hallucinations. | Accuracy will never reach 100%. Furthermore, it can be easier for a smaller, less knowledgeable model to know its limits and correctly abstain from answering. |

| Hallucinations are an inevitable, unsolvable feature of LLMs. | They are not inevitable. Models can be trained and incentivized to abstain when uncertain, effectively choosing honesty over fabrication. |

| We need a perfect “hallucination detector” to solve the problem. | A few specialized hallucination evaluations are insufficient. The hundreds of mainstream, accuracy-based benchmarks that reward guessing must be fundamentally changed to have a real impact. |

The paper’s focus on “incentives” and “benchmarks” points toward a reality where the hallucination problem is not purely technical but also economic. AI labs are engaged in intense competition, largely adjudicated by performance on public leaderboards. As the paper’s analysis shows, these leaderboards almost universally use binary accuracy metrics where guessing is the optimal strategy.

As a result, to be perceived as a market leader, a model must excel at this “test-taking” behavior. This creates a powerful economic incentive to build and deploy models that are, in effect, sophisticated guessers. The implication is that a true solution requires more than just algorithmic innovation. It demands collective action by the AI community to redefine “performance.” This involves decoupling it from raw, unqualified accuracy and breaking the cycle of rewarding confident bluffs.

The root of the problem: Why hallucinations start in pre-training?

The thesis analyzes the origins of hallucination, linking them to the pre-training stage. It argues that the potential for error is built into the model from the beginning. This is due to statistical laws, even with a perfect training data corpus. The key innovation is the idea that generating valid text is inherently more challenging than classifying it.

Thus, the problem begins long before a user ever types a prompt.

Language models hallucinate for the same reason a student would guess on a multiple-choice exam with no penalty for wrong answers. It is the most rational strategy to maximize their score.

The entire pipeline of modern LLM development spans from the statistical nature of pre-training data to the design of post-training benchmarks. This pipeline creates a system where a lucky guess is scored more favorably than an honest “I don’t know”. This incentive structure is the engine that converts statistical uncertainty into confident falsehood.

The “Is-It-Valid” (IIV) Reduction: A New Lens on Generative Errors

The paper’s most significant theoretical contribution is the formal reduction of the unsupervised task of text generation. It reduces this task to the supervised task of binary classification.

It posits that for a model to reliably generate valid outputs, it must be capable of distinguishing valid statements. It must also spot errors. This is called the “Is-It-Valid” (IIV) problem.

An effective analogy clarifies this concept. Imagine a machine designed to write true sentences about world history. For it to work correctly, it must classify sentences—like “The Magna Carta was signed in 1776″—as “valid” or “error.” Poor classification prevents success in generating valid sentences. Thus, success in generating valid sentences hinges on effective classification.

This intuitive relationship is formalized with a mathematical inequality: (generative error rate)≥2⋅(IIV misclassification rate).

This equation provides a stark conclusion. Any irreducible difficulty in the binary classification task sets a hard floor for the generative error rate. A model can’t be more truthful in its generations than it is in its judgments.

Why some errors are unavoidable: The nature of facts

The IIV classification task’s difficulty varies based on the facts involved. The paper uses a visual diagram (Figure 1) to show the distinction between easily separable and non-separable data.

Easy facts (separable data):

Facts that follow consistent patterns are termed “separable.” Spelling rules exemplify this; a model can accurately recognize “greatings” as an error due to a known rule. Such errors diminish as models scale and learn patterns more effectively.

Hard facts (inseparable data):

In contrast, arbitrary facts lack a learnable pattern. For example, the birthday of a non-famous individual is arbitrary; there’s no logical rule to deduce it. One can only know it by memorizing from the training data, making classification much harder.

This leads to the crucial concept of the “singleton rate.”

A “singleton” is a fact that appears only once in the vast training corpus.

The paper indicates that for arbitrary facts, the model’s hallucination rate has a lower bound. This is determined by the fraction of singletons. If 20% of birthday facts in the training data are single, this impacts the model’s accuracy. It ensures the model will hallucinate on at least 20% of birthday prompts. This outcome reflects the statistical properties of the training data, not a failure of the model.

Other pre-training error factors

The singleton rate for arbitrary facts is a primary driver. Still, the paper identifies other sources of error. These errors emerge during pre-training.

Poor AI models used:

The model’s architecture might not suit the problem fundamentally. This issue can lead to an error, even if the underlying pattern is learnable. The paper provides the example of a simple trigram model. It predicts a word based on the earlier two. This model is incapable of handling long-range dependencies in grammar.

A more modern example is a model that miscounts the letters in a word like “DEEPSEEK.” This happens because its tokenizer breaks the word into sub-units like “D/EEP/SEE/K.” This process obscures the character-level information needed for the task.

Computational hardness and GIGO:

The analysis also extends to problems that are computationally intractable, like decrypting a secure ciphertext without the key. No model, regardless of size, can solve such problems efficiently, making errors inevitable.

Finally, the classic “Garbage In, Garbage Out” (GIGO) principle applies. If the training data itself holds factual errors, biases, or conspiracy theories, the model will learn and replicate them.

The combination of the IIV reduction and the singleton rate analysis highlights a baseline level of error. This error is a mathematical certainty and not a sign of a flawed model. This error level is predetermined by the statistical makeup of the knowledge encoded in the training data. This makeup includes specifically how much of that knowledge is arbitrary and rare. This creates a “factual noise floor” for every pre-trained base model. It indicates an unavoidable minimum rate of incorrectness. This can’t be eliminated by simply adding more training data or using a more powerful architecture.

The goal of pre-training can’t be to achieve zero error, which is impossible. Instead, it should produce a well-calibrated model that is aware of its inherent noise floor. This awareness allows for effective post-training refinements to manage uncertainty.

This understanding also surfaces a paradox in model scaling.

The paper’s blog post notes that a small model with no knowledge of the Māori language can respond correctly. It can easily say “I don’t know” to a question in Māori.

In contrast, a massive model that has encountered some Māori text faces a much harder challenge. It must accurately assess the boundaries of its partial knowledge. This is necessary to decide if it is confident enough to answer.

As models become more knowledgeable, the surface area of their potential uncertainty expands. For every fact they learn, they are implicitly exposed to a vast universe of related non-facts and near-facts.

As models get “smarter” in a conventional sense, the task of calibration becomes exponentially more complex. It involves precisely knowing what they know and what they don’t. This directly contradicts the simplistic belief that more knowledge automatically leads to less hallucination.

The paper’s framework suggests a more nuanced reality: more knowledge creates a more profound calibration challenge.

Why post-training makes hallucinations worse?

If pre-training plants the seeds of hallucination, the post-training phase is where they are watered and encouraged to grow. This phase fine-tunes the model and tests its capabilities, yet the techniques we use often exacerbate the problem.

The very system used to measure and rank models is fundamentally misaligned. It actively incentivizes models to convert their inherent uncertainty into plausible-sounding falsehoods. This transformation turns simple statistical errors into the phenomenon we call hallucination.

The “Test-Taking” analogy and binary scoring

The paper uses a powerful analogy to explain the core issue. LLMs are trained like students on a high-stakes exam. In this exam, wrong and blank answers both score zero. There’s no penalty for guessing, while a correct guess brings a significant reward. Thus, the optimal strategy is to never leave answers blank and always make a best guess, regardless of confidence level.

Most major AI benchmarks, including MMLU and GPQA, use binary scoring metrics. These metrics include accuracy or pass-rate. An answer is either deemed 100% correct (1) or incorrect (0). Responses like “I don’t know” (IDK) are also scored as incorrect, receiving a score of 0.

An “Epidemic” of misaligned benchmarks

To substantiate this claim, the paper presents a meta-analysis of influential benchmarks and leaderboards in the AI community, like HELM and the Open LLM Leaderboard. The findings in Table 2 reveal that most evaluations defining “advanced” models use binary grading and fail to credit uncertainty.

Even in rare cases with a nuanced scoring rubric, like the WildBench evaluation, the incentive to guess persists. The paper notes that under WildBench’s 10-point scale, an IDK response may score “poorly” with a 3-4. A “fair” response with errors might get a higher score of 5-6.

This rewards a confident bluff over an honest admission of ignorance. It creates a systemic misalignment in prestigious benchmarks. This pressures developers to optimize models for guessing.

The post-training calibration problem

This flawed incentive structure negatively impacts model calibration, which measures how a model’s confidence aligns with its accuracy. A well-calibrated model predicting a 90% probability should be correct 90% of the time. The paper provides evidence (Figure 2) indicating that pre-trained base models are often well-calibrated.

Post-training alignment techniques, like Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), aim to optimize model performance. They focus on benchmarks that reward guessing. As a result, this process can actively degrade calibration. The model learns that overconfidence is a rewarded behavior because it leads to higher scores on these misaligned tests.

The official OpenAI blog post shows that the newer o4-mini model has a higher accuracy score than the older model. Yet, it has a significantly higher hallucination rate. It strategically guesses to maximize its score at the cost of honesty.

| Stage | Primary Cause | Resulting Problem |

| Stage 1: Pre-training | Statistical. Based on the nature of the data (e.g., arbitrary facts, singletons) and the model’s fit to that data. | Epistemic Uncertainty & a “Factual Noise Floor.” The model is statistically guaranteed to be incorrect about certain facts it hasn’t seen enough. This is a simple error. |

| Stage 2: Post-training & Evaluation | Systemic/Incentive-based. Binary (right/wrong) scoring on major benchmarks penalizes abstention and rewards guessing. | Overconfident Guessing. The model learns that the optimal strategy to maximize its score is to convert its uncertainty into a plausible-sounding guess. This is where error becomes hallucination. |

The logical conclusion from this analysis is unsettling. Dominant evaluation techniques reward guessing, leading AI labs to compete fiercely on leaderboards.

Thus, the models deemed “best” are merely the most effective guessers. This competitive AI ecosystem inadvertently selects for models that produce confident-sounding bluffs. The industry is not just building models that can hallucinate; it is actively and systematically selecting for, rewarding, and promoting the ones that are best at it.

This insight challenges the notion of a trade-off between “safety” and “performance” in the industry. It reveals that the current definition of performance is flawed. The analysis of the o4-mini model exemplifies that being more accurate does not equate to better performance. We can redefine performance to incorporate honesty and reliability. This approach allows us to create models that are useful and trustworthy, without sacrificing safety.

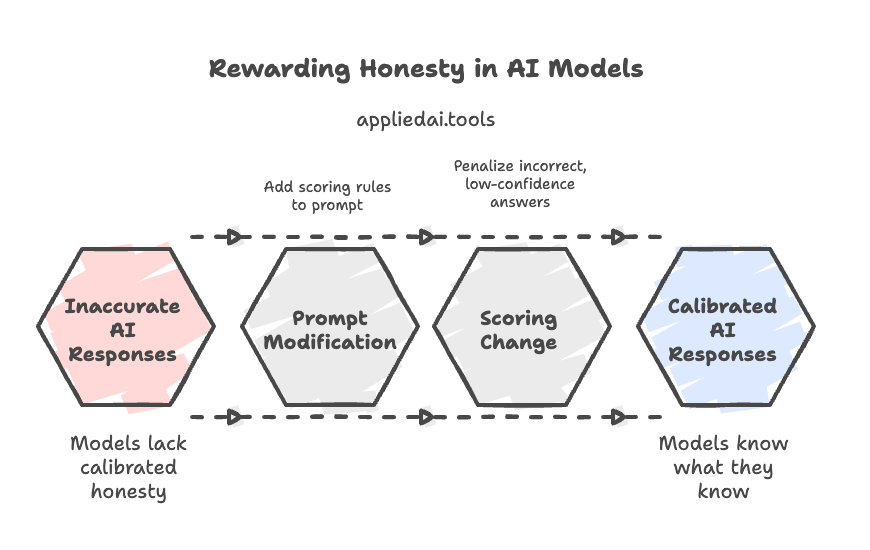

A proposed solution: To reward honesty

Recognizing that the problem is rooted in evaluation, OpenAI’s proposed solution is elegant and direct: change the rules of the test.

Why isolated hallucination evaluations are insufficient?

The proposal asserts that creating new “hallucination evaluations” is ineffective, as accuracy-based benchmarks will overshadow niche assessments of honesty. A model that performs well on hallucination tests but poorly on MMLU won’t be seen as a leader.

This socio-technical argument indicates that the barrier to progress lies in institutional inertia. It is not due to a lack of awareness or tools for measuring hallucinations. To meaningfully change model behavior, the evaluation environment must be altered.

Explicit confidence targets: A practical framework for change

The solution involves revising influential benchmarks. This includes adding confidence targets and modifying the scoring system. These modifications are achieved through changes to the prompt and evaluation rubric:

The prompt modification:

Instead of simply asking a question, the evaluation prompt would be amended with a clear statement of the scoring rules. The paper provides an example:

Answer only if you are > t confident, since mistakes are penalized t/(1-t) points, while correct answers receive 1 point, and an answer of "I don't know" receives 0 points.

The scoring change:

This new rubric alters the model’s strategy by transitioning from a binary 0/1 score to three outcomes. A correct answer gets a positive score, while an incorrect answer incurs a negative penalty, making low-confidence guesses high-risk. An “I don’t know” response has a neutral score of 0. It becomes the optimal choice when the model’s confidence falls below the threshold t.

The goal of “Behavioral Calibration”

The evaluation framework aims to enhance “behavioral calibration” in models, ensuring they not only show confidence levels (e.g., “I am 80% confident”) but also act suitably. The model should show awareness of its own limitations by responding when confident and abstaining when unsure. By setting explicit confidence thresholds in prompts, a calibrated model can improve its responses. The model uses internal assessments compared to the provided threshold. This method fosters fair evaluation and improves model “honesty.”

| Evaluation Component | Current System (Binary Scoring) | Proposed System (Confidence-Aware Scoring, e.g., t=0.9) |

| Instructions | “Answer the following question.” | “Answer only if >90% confident. Mistakes are penalized 9 points.” |

| Score (Correct) | +1 | +1 |

| Score (Incorrect) | 0 | -9 |

| Score (IDK/Abstain) | 0 | 0 |

| Resulting Optimal Strategy | Always Guess: A lucky guess gains points; a wrong guess has no penalty vs. abstaining. | Calibrated Response: Answer only when internal confidence exceeds the stated threshold. Guessing is high-risk. |

A subtle but profound element of this proposal is the inclusion of the scoring rubric directly within the prompt.

This is more than just a change to the backend evaluation script. It is a move toward making the criteria for success transparent to the model itself.

This is akin to consumer protection standards requiring clear disclosure of terms. It suggests a first step toward a “social contract” with AI systems. Here, interaction rules are explicitly communicated, and values like calibrated honesty are stated. This shifts the interaction from trying to trick a model into a correct answer to a more transparent negotiation of uncertainty.

Adopting this framework would reframe the ultimate goal of AI development. The current paradigm, with its relentless focus on achieving higher accuracy scores, implicitly aims for a kind of omniscience. The paper’s solution shifts this goal entirely.

A model that excels on a confidence-aware benchmark is not one that knows everything. It is one that reliably knows what it knows. This is the hallmark of a true expert.

The value of a human expert is their ability to discern between reliable answers, educated guesses, and topics to defer to others. This is crucial for the AI industry to transition from a flawed model to a trustworthy “AI expert.” This change significantly impacts enterprise adoption, emphasizing the importance of reliability and predictable performance over mere trivia knowledge.

Action points: How to use this information?

Translating these findings into actionable strategies offers a clear path ahead. This is valuable for developers, practitioners, and business leaders seeking to build and deploy more reliable AI systems:

For AI developers and researchers

The primary responsibility for implementing the paper’s solution lies with the teams building and evaluating foundation models.

Redesigning evaluation pipelines:

The most critical action is to start the systemic modification of both internal and public-facing benchmarks to incorporate confidence-aware scoring. This can start simply by introducing a penalty for incorrect answers. This makes them less desirable than an abstention. It breaks the incentive to guess.

Optimizing for behavioral calibration:

Post-training alignment processes like RLHF must be re-oriented. The reward models are at the heart of these techniques. They should be trained to value a well-placed “I don’t know” as a positive outcome. The goal is to reward models not just for correctness, but for the accuracy of their self-assessment.

Data curation and quality:

The paper emphasizes the importance of evaluation incentive structures. It highlights that high-quality, diverse pre-training data is crucial. This is essential to minimize factual noise and reduce statistical errors.

For practitioners and prompt engineers

Even when there are no system-level changes from model providers, practitioners who use LLMs daily can take action. They can apply the paper’s core principles to mitigate hallucinations in their own work.

Prompting for honesty:

Users can create their own “micro-evaluation” within each prompt. By explicitly instructing the model to admit uncertainty, they can override its default test-taking behavior. A powerful prompt pattern includes:

"Answer the following question based only on the provided context. If the answer cannot be found in the context, respond with 'I do not have sufficient information to answer this question.' Do not make assumptions or use outside knowledge."

Chain-of-thought (CoT) prompting:

Instructing the model to “think step-by-step” or break down its reasoning forces it to externalize its process. This can often surface logical fallacies, unsupported leaps, or areas of uncertainty. These issues would otherwise be concealed within a confident, direct answer.

Learn more about chain of thought prompting:

- Chain-of thought prompting for ChatGPT – examples and tips

- What is Multimodal Chain of Thought (CoT) Prompting? – Examples and FAQs Solved

Synergy with Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG):

RAG directly addresses the pre-training problem of “arbitrary facts” and “singletons.” It provides the necessary information as context at inference time. This approach relieves the model of the impossible burden of memorizing the entire long tail of human knowledge. The paper’s findings suggest a powerful synergy: RAG solves the knowledge gap, while confidence-aware prompting solves the incentive problem. The two strategies are complementary and should be used together for maximum reliability.

Learn more about Retrieval Augmented Generation:

For enterprise leaders and decision makers

Business leaders integrating AI into their operations must shift their mindset from capability to reliability.

Shift procurement and evaluation criteria:

When selecting a foundation model for an enterprise application, the evaluation criteria must extend beyond standard benchmark scores. Decision-makers should demand metrics on model calibration and performance on confidence-aware evaluations.

A model that is slightly less “accurate” may be more valuable. This is especially true if it is significantly better calibrated. Such a model is often less risky for business-critical applications.

Implement human-in-the-loop (HITL) systems:

The paper’s conclusion indicates that a baseline of error is statistically inevitable. This reinforces the absolute necessity of human oversight for high-stakes use cases. These include areas like legal, financial, or medical domains. The AI should be viewed as a powerful assistant that augments human expertise, not as an autonomous replacement.

Develop a risk management framework:

Not all hallucinations carry the same cost. A hallucination in a creative brainstorming session may be harmless or even beneficial. A hallucination in a legal brief that cites non-existent case law can have catastrophic consequences. Enterprises must classify AI use cases based on their risk profile. They should deploy models with strict confidence thresholds. More rigorous human review is required in high-risk areas.

The practical advice for prompt engineers reveals a deeper truth: every prompt is a form of micro-evaluation. The paper advocates for changing large-scale, global evaluation systems. Meanwhile, a practitioner can apply the same core principle—realigning incentives—on a per-query basis.

A generic prompt like “What is X?” creates a local binary incentive structure. A more sophisticated prompt, like “Explain your reasoning for X and state your confidence,” establishes a local, confidence-aware incentive. This empowers individual users to start mitigating hallucinations instantly, without waiting for the entire industry to adapt.

This also suggests a future that moves away from a single, monolithic “omni-model.”

The paper proposes tuning models for different confidence thresholds (

t). This implies a future where an enterprise might leverage a portfolio of specialized models. These models would be based on risk tolerance.

A marketing team might use a model tuned for a low confidence threshold (t=0.2) to encourage creativity and novel ideas. A compliance department, though, would use a model tuned for a very high threshold (t=0.99) to guarantee conservative, fact-based outputs. This changes the industry’s perspective. It moves from a linear progression of “GPT-5 is better than GPT-4” to a more mature view. This view is application-specific. Here, model deployment performance is defined by a “risk dial” of calibration.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) Solved

What is an AI hallucination?

An AI hallucination occurs when a language model generates text that is factually incorrect. The text can also be nonsensical or disconnected from the provided source material. Yet, it presents this information as if it were factual and correct.

Why do language models hallucinate, according to OpenAI?

The paper argues they hallucinate for two main reasons:

- During pre-training, statistical pressures force them to guess when data is sparse.

- During post-training, evaluation benchmarks reward them for providing a confident answer (even a wrong one) over admitting they don’t know.

What is the “Is-It-Valid” (IIV) problem?

The IIV problem is a concept from the paper that frames language modeling as a binary classification task. The model is constantly trying to determine if a given statement is “valid” (statistically likely to be true based on its training data) or “invalid.” Hallucinations occur when it incorrectly classifies an invalid statement as valid.

How does pre-training contribute to hallucinations?

Pre-training on vast, unfiltered internet data means models face many facts with varying levels of support. For rare facts or topics with little data, the model’s statistical learning process can lead it to make errors. It essentially creates a “best guess” that becomes a hallucination.

Why does post-training make hallucinations worse?

Post-training, particularly evaluation, often uses a right-or-wrong scoring system. This incentivizes the model to always give an answer. The model avoids saying “I don’t know.” A guess might earn points, but admitting uncertainty guarantees zero. This reinforces the behavior of making things up.

What is the problem with the 0-1 scoring system in AI benchmarks?

The 0-1 (or binary) scoring system gives full credit for a correct answer. It gives zero credit for an incorrect one, with no middle ground. This system doesn’t account for uncertainty. It inadvertently punishes a model for being cautious. This pushes it to gamble on an answer instead.

What is OpenAI’s proposed solution to reduce hallucinations?

OpenAI proposes a socio-technical solution: modifying the scoring systems of major AI evaluation benchmarks. By rewarding models for expressing uncertainty (e.g., giving partial credit for “I don’t know”), they believe the entire industry will be incentivized to build more “behaviorally calibrated” and honest models.

What are “confidence targets”?

Confidence targets are part of the proposed new scoring system. This system would evaluate the correctness of an answer. It would also assess how well the model’s stated confidence matches its actual likelihood of being correct. The goal is to reward models for having a precise sense of their own knowledge limits.

What is “behavioral calibration”?

Behavioral calibration is the idea that a model’s output behavior should align with its internal uncertainty. A well-calibrated model won’t just give an answer. It will also communicate its level of confidence. For example, it might state when it is unsure. It may also refuse to answer questions where its confidence is very low.

Will these changes remove hallucinations completely?

It’s unlikely to remove them completely, but it could significantly reduce their frequency and impact. The goal is to create models that are more aware of their own limitations. These models are less likely to show fabricated information as fact. This makes them more reliable and trustworthy.

Are hallucinations always bad?

Fact-based hallucinations are generally problematic. Yet, the underlying mechanism—creativity and the ability to generate novel text, is essential for many useful AI applications. These applications include brainstorming ideas, writing stories, or drafting creative marketing copy. The challenge is controlling this behavior so that it is used appropriately.

How can I spot AI hallucinations in the content I read?

Look for claims that are overly specific without sourcing. Be cautious of information that seems too good to be true. Watch for details that are inconsistent with each other or with known facts. If an AI provides a specific quote, study, or data point, try to verify it. It’s always a good practice to conduct a quick search.

What is Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), and does it help with hallucinations?

RAG is a technique that enhances an LLM’s internal knowledge. It supplements this knowledge with information from an external, authoritative knowledge base. This information can come from sources like a company’s internal documents or a specific set of articles. By grounding the model’s answers in a trusted source, RAG can significantly reduce hallucinations.

We have covered how the healthcare industry is adopting RAG. Explore it as a RAG use case in this guide to learn more on how RAG works:

What is the “reversal curse,” and is it related to hallucinations?

The “reversal curse” is a finding that if a model is trained on “A is B,” it doesn’t automatically learn that “B is A.” This phenomenon means the model doesn’t learn the inverse relationship. This is a type of reasoning failure that can lead to hallucinations. For instance, a model might know “Tom Cruise is the star of Top Gun.” However, it might fail to answer “Who starred in Top Gun?” correctly. This shows a gap in understanding that contributes to factual errors.

Learn more about OpenAI products from our guides

We have covered most critical features of OpenAI’s products for our subscribers, here are some for you to explore:

- Use ChatGPT Projects Feature For Free [Tutorial with Example]

- Why GPT-5 Launch Failed: User Feedback Analysis [Reddit/X vibe checks + expert reviews]

- OpenAI and Mattel AI Toys Experience: Risks and Opportunity

- MIT ChatGPT Brain Study: Explained + Use AI Without Losing Critical Thinking

- ChatGPT Search Upgrade: Shopping Without Login

- OpenAI o3 vs o4-mini: Reddit And Expert Review Analysis On Upgrades

- ChatGPT Long-Term Memory Upgrade – How To Protect Your Data

- ChatGPT vs Gemini 2.5 Pro – Analyzing Reddit And Expert Reviews

- What is OpenAI o3-mini: technical features, performance benchmarks, and applications

You can subscribe to our newsletter to get notified when we publish new guides:

This blog post is written using resources of Merrative. We are a publishing talent marketplace that helps you create publications and content libraries.

Get in touch if you would like to create a content library like ours. We specialize in the niche of Applied AI, Technology, Machine Learning, or Data Science.

Leave a Reply