Since the launch in 2023, interaction with Generative AI primarily involved ‘prompt engineering’. Nonetheless, as we advance toward AI agents in 2025, the focus is shifting to ‘context engineering’.

Prompt engineering revolves around crafting textual inputs to get desired outputs from models, combining intuition and trial-and-error. It emphasizes linguistic nuances.

Applications have evolved from simple chatbots to complex AI agents that can execute code and manage workflows. Models like Gemini 3 highlight the limitations of manual prompting.

Now, the performance bottleneck lies in assembling the information environment rather than phrasing a single query.

‘Context Engineering’ focuses on optimizing the environment where questions are posed, rather than just the questions themselves. It involves programmatically assembling all the tokens perceived by the LLM, including documents, memory, system instructions, and execution history.

Technically, context engineering is the system-level architecture that turns simple LLMs into reliable, production-grade AI agents.

I have shared detailed overview of what is context engineering with examples of approaches by OpenAI, Anthropic, and LangChain:

This guide breaks down the four essential strategies. These include Write, Select, Compress, and Isolate. They are needed to manage the finite context window. These strategies prevent expensive failures in complex AI systems.

Key takeaways:

- Build Systems, Not Strings: Stop tweaking prompts and start engineering pipelines. Context engineering dynamically assembles the perfect ‘briefing’ for your AI—combining instructions, RAG data, and tools, before every single interaction.

- Master the Four Pillars: Scale your agents using four proven architectural patterns:

- Write: save state to memory

- Select: retrieve only relevant data

- Compress: summarize history

- Isolate: delegate tasks to sub-agents

- Respect the ‘Attention Budget’: The context window is finite and expensive. Prevent ‘Context Rot’ (where models ignore data). Strictly filter noise. Enhance for high signal-to-noise ratios. Do this instead of dumping raw data.

What drives the need for context engineering?

The emergence of context engineering is driven by two primary factors:

- Finite nature of the context window

- Increasing complexity of agentic tasks

Despite the advent of models with context windows exceeding one million tokens, like Gemini 3 or Claude 3.5 Sonnet, the context window remains a constrained resource, both economically and computationally. LLMs show ‘U-shaped’ attention curves. Here, information buried in the middle of a massive context window is statistically more likely to be ignored. This is a phenomenon known as ‘lost in the middle’.

Learn more about Lost in the Middle concept from this AI research paper:

Lost in the Middle: How Language Models Use Long Contexts

Furthermore, the cost of processing input tokens scales linearly with context length. This makes the indiscriminate dumping of data into the window financially unviable for production systems.

As a result, context engineering fundamentally presents as a resource optimization problem.

It involves making high-stakes architectural decisions about:

- What to include and what to exclude

- How to format information to maximize the model’s reasoning capabilities while minimizing latency and cost

The transition from ‘vibe coding’ prompts to engineering robust context pipelines highlights the maturation of AI development. It has evolved from an experimental art form into a rigorous software engineering discipline.

Defining the scope of Context Engineering

Context engineering encompasses the entire lifecycle of data as it interacts with the model. It is distinct from prompt engineering in its scope and mechanism.

Prompt engineering involves tweaking a sentence to make it more polite or precise, context engineering includes several complex tasks:

- Design the database schemas for long-term memory.

- Implement retrieval algorithms that select the most relevant tools for a given task.

- Architect the state machines that track an agent’s progress through a workflow.

The discipline can be categorized into several distinct frameworks found in contemporary research and industry literature:

- The Functional Taxonomy: Categorizing operations into Writing, Selecting, Compressing, and Isolating context, a model popularized by LangChain context engineering.

- The Component Taxonomy: Breaking down context into System Instructions, Tools, Knowledge (RAG), and State/History.

- The Static vs. Dynamic Spectrum: Distinguishing between immutable system parameters and ephemeral, runtime-generated data.

By examining these frameworks, we create a unified vocabulary for discussing the architecture of intelligent agents.

First, what is context window?

One must first understand the physical and architectural constraints of the Large Language Model. This knowledge helps in grasping the necessity of context engineering.

The ‘Context Window’ is a tangible limit. It is defined by the model’s architecture. This includes the attention mechanism and the Key-Value (KV) cache.

The Finite Attention Budget

Modern Transformers are the architecture underpinning nearly all LLMs. They rely on a mechanism called self-attention. This mechanism weighs the importance of different words in a sequence compared to each other.

Learn more about self-attention in this iconic AI research paper by Google:

What is context rot or context distraction?

The theoretical capacity of these context windows has grown exponentially. Nonetheless, the effective attention budget—the model’s ability to actually use that information—has not scaled perfectly linearly. Research consistently demonstrates that model performance degrades as the context fills with irrelevant information. This concept is referred to as ‘Context Rot’ or ‘Context Distraction’.

When a context window is filled with superfluous tokens, the model’s attention mechanism becomes diluted. It may focus on irrelevant details. In the case of ‘Context Poisoning,’ it may latch onto hallucinated or incorrect information found in the history. This reinforces errors in a feedback loop. Thus, the primary goal of context engineering is to maximize the ‘signal-to-noise’ ratio within the window. It is about finding the smallest possible set of high-signal tokens that maximize the likelihood of a desired outcome.

The KV-Cache and Latency

At a mechanical level, the cost of context is also measured in latency.

During inference, the model computes Key and Value matrices for the input tokens. These are stored in the KV-cache to avoid re-computation during the generation of subsequent tokens. Effective context engineering leverages this mechanism by designing prompts that are ‘prefix-stable.’

If the initial portion of a prompt (e.g., the system instructions and tool definitions) remains constant across requests, the inference engine can reuse the cached KV states. This dramatically reduces Time to First Token (TTFT) and computational cost.

Conversely, if the context is dynamically assembled in a way that changes the prefix for every request (e.g., by inserting a timestamp at the very beginning), the cache is invalidated. The model must re-process the entire sequence.

Thus, context engineering involves not just what is put in the window. It also involves where it is placed to improve cache hits.

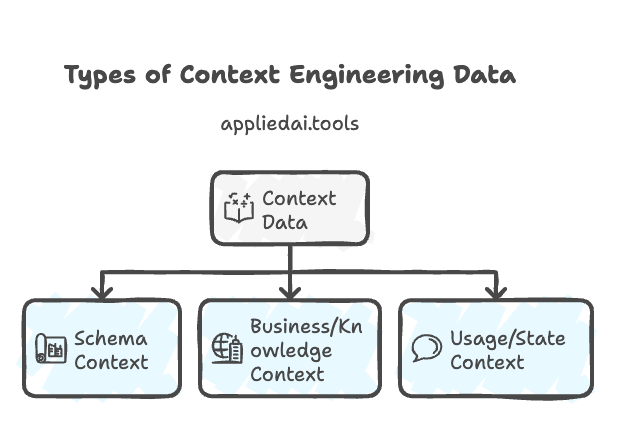

The Three Types of Context Data

Understanding the different types of data that populate the window is crucial for effective assembly. Here are the three primary categories of context data:

- Schema Context: This includes the structural definitions required for the model to operate. Examples include table names in a Text-to-SQL task, tool definitions in an agentic workflow, or the JSON schema for structured output. Without this, the model is functionally blind to the environment’s constraints.

- Business/Knowledge Context: This encompasses the semantic definitions and facts relevant to the domain. An example is defining what ‘revenue’ means in a specific corporate context. Another example is retrieving the company’s travel policy. This is often the domain of RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation).

- Usage/State Context: This includes few-shot examples of successful queries, the current conversation history, and the transient state of the agent. This provides the model with the trajectory of the current task.

Types of Context Engineering #1: Write Context

The “Four Pillars” framework, crystallized by LangChain, categorizes context engineering strategies into Write, Select, Compress, and Isolate.

The first of these, ‘Write Context,’ addresses the impermanence of the LLM’s generation. Once a model generates a token, it exists only in the transient history of that specific inference chain. “Writing” context transforms this transient data into persistent assets, effectively externalizing memory to reduce cognitive load on the model.

Scratchpads: The Cognitive Workspace

The ‘scratchpad’ technique provides the model with a designated area to ‘think.’ It allows the storage of intermediate values that should not clutter the main conversational thread. These values should not be lost if the context is trimmed. In complex reasoning tasks, an agent may need to conduct intermediate calculations. It may also need to store the result of a tool call necessary for the next step. This result does not need to be permanently embedded in the prompt history.

By writing these to a scratchpad—often implemented as a specific tool (e.g., update_scratchpad(content)) or a reserved section of the system prompt that is updated programmatically—the system preserves the data without clogging the main conversational thread.

For example, in the Manus agent system, the agent is architected to constantly rewrite a todo.md file.

This file acts as a ‘forcing function’ for attention. It ensures the model remains grounded in its global plan. This happens even as it executes low-level local tasks. This externalization of the plan allows the model to ‘refresh’ its understanding of the overall objective at every step. It prevents the ‘drift’ that often occurs in long-horizon tasks.

Structured State and Persistence

Writing context extends beyond simple text notes to the generation of structured artifacts. Advanced context engineering involves defining strict schemas for the agent’s state. Developers use JSON or XML objects to track variables like current_step, verified_facts, and pending_tasks.

This structured state serves as a bridge between the probabilistic world of the LLM and the deterministic world of software. When an agent writes to a state object, it is essentially committing to a decision.

Reflexion:

A powerful application of writing context is ‘Reflexion,’ where an agent writes a summary of its performance after a task. This summary is indexed and retrieved when similar tasks are encountered in the future. This process allows the system to ‘learn’ from its mistakes without retraining the underlying model.

Semantic Memory:

Writing context also encompasses the creation of long-term memories about the user. If a user mentions they prefer Python over Java, the system writes this fact to a vector database or a user profile. In future sessions, this fact is retrieved, creating a sense of continuity and personalization.

The ‘Mask, Don’t Remove’ Principle

A sophisticated variation of writing context is the “Mask, Don’t Remove” principle observed in high-performance agents like Manus.

When dealing with a large action space (e.g., hundreds of available tools), naively adding or removing tool definitions from the context window can invalidate the KV-cache. This confuses the AI model. Instead, the system keeps the tool definitions in the context. It writes them once but uses a state machine to ‘mask’ the token logits during decoding.

This ensures that the model can only select valid actions for the current state. It effectively ‘writes’ constraints into the execution layer rather than the prompt layer. This technique maintains cache stability while enforcing strict behavioral guardrails.

Types of Context Engineering #2: Select Context

‘Select Context’ is the gatekeeper of the window. It involves pulling information into the context from external sources.

Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) is the most well-known implementation of this pillar. However, context engineering extends the concept of selection. It applies to tools, memories, and system instructions.

Learn more about RAG from our deep dive on its concept here:

Beyond Naive RAG: Precision Retrieval

Standard RAG, which retrieves documents based on simple cosine similarity, is often insufficient for robust context engineering.

A ‘naive’ implementation may retrieve documents that share keywords with the query. But, these documents might lack the necessary semantic depth. This can lead to ‘Context Confusion’. Advanced selection strategies include:

Hybrid Search:

Combining keyword-based search (BM25) with semantic vector search serves two main purposes. First, it ensures that specific identifiers, like error codes or product IDs, are matched exactly. Second, it captures conceptual relevance.

HyDE (Hypothetical Document Embeddings):

This technique addresses the mismatch between short user queries and long documents. The system uses an LLM to generate a hypothetical answer to the user’s query. It embeds that hypothetical answer. Then, it uses that vector to search the database. This often yields significantly better retrieval alignment.

Reranking:

A critical step in modern context pipelines is the use of a Cross-Encoder model. After retrieving a broad set of candidates (e.g., 100 documents), the Cross-Encoder scores each one against the query for relevance. Only the top-scoring chunks are “selected” for the context window. This ensures that the limited token budget is spent only on the highest-quality information.

Tool Loadout and Dynamic Capabilities

In agentic systems with extensive capabilities, like an enterprise agent with access to Jira, GitHub, Salesforce, and Google Drive, listing every available tool definition in the system prompt takes up the entire context window. This would degrade reasoning performance. This necessitates ‘Tool Selection’ or ‘Tool Loadout’.

The mechanism typically involves a two-stage process.

First, a lightweight ‘router’ or ‘classifier’ model analyzes the user’s query to predict the category of tools needed (e.g., Issue Tracking vs. CRM). Based on this prediction, the system dynamically loads only the relevant tool definitions (e.g., Jira tools) into the context, explicitly excluding irrelevant ones. This ‘Just-in-Time’ (JIT) context loading keeps the window lean and focused. It prevents the model from being distracted by capabilities it doesn’t need for the current turn.

I found this lecture on Tool Loadout in context engineering that you can learn more from:

Progressive Disclosure

Anthropic’s research highlights the strategy of ‘Progressive Disclosure’ as a key element of context selection.

Instead of dumping all retrieved information into the context at once, the agent is given a ‘map’. It is high-level summary of the available data (e.g., file paths, document titles) and a set of retrieval tools. The agent then autonomously decides which specific pieces of information to ‘select’ and read into its context.

This mimics human research behavior. We do not read every book in the library before answering a question. Instead, we browse the catalog, select relevant titles, and then read specific chapters. The agent is empowered to drive the selection process. This empowerment helps the system avoid ‘Context Overload.’ It allows the agent to build its understanding layer by layer.

Experts say, progressive disclosure may replace the need for MCP:

Types of Context Engineering #3: Compress Context

The ‘Compress’ strategy addresses the economic and technical limits of LLMs. Even if a model can process a million tokens, doing so is often slower and costlier. Compression is the strategic trade-off of fidelity for space, essential for long-running agents that would otherwise hit hard token limits.

Summarization Architectures

The most common form of compression is summarization. Yet, within context engineering, this is applied architecturally rather than just textually.

Recursive Summarization:

For extremely long documents or histories, the system breaks the text into chunks. It summarizes each chunk. Then it summarizes those summaries. This creates a hierarchical tree of context. The model can access the high-level summary. It can ‘drill down’ into specific details if needed.

Conversational Compaction:

Systems like Claude Code implement “Auto-Compact” mechanisms. When the context utilization hits a defined threshold (e.g., 90% of the limit), the system triggers a compaction routine. It takes the older part of the message history and distills it into a concise narrative summary (e.g., “User asked for X; Agent tried Y and failed; Agent is now trying Z”). This summary replaces the raw message logs, maintaining the semantic thread of the conversation while freeing up thousands of tokens.

The art of compaction lies in heuristic design—knowing what to keep (decisions, facts) and what to discard (failed tool calls, verbose formatting).

Pruning and Trimming

Context trimming involves the heuristic-based removal of tokens that are no longer relevant. This helps prevent ‘Context Poisoning,’ where an agent fixates on past errors.

Error Pruning:

If an agent makes a syntax error in a SQL query, they might correct it in the next turn. The tokens describing the error are often no longer needed. The error message is also often unnecessary. A sophisticated context engine will remove this failed branch from the history. It presents the model with a clean slate. This slate holds only the successful logic.

Tool Output Truncation:

When a tool returns a massive dataset (e.g., a list of 10,000 users from a database), injecting the full JSON into the context would be catastrophic. Context engineering involves implementing middleware that intercepts this output and truncates it (e.g., keeping the first 5 items) with a systemic note: “…and 9995 more items. Refine your query to see specific users.” This forces the agent to use more precise queries rather than relying on the model to parse massive datasets.

Visual and Multimodal Compression

As agents become multimodal, compressing visual context becomes critical. Video data, for instance, is incredibly token-dense. Context engineering for video involves converting visual data into descriptive text, structured metadata, or vector embeddings (“Write Context”) before selection.

- Frame Sampling: Instead of processing every frame, the system might sample frames at 1fps. Another approach is to sample only when scene changes are detected.

- Captioning: A specialized vision model generates textual captions for key frames. These text captions, rather than the image tokens, are fed to the reasoning agent. This reduces the context load by orders of size while retaining the semantic content of the video.

Types of Context Engineering #4: Isolate Context

The “Isolate” pillar is the most architectural of the strategies. It recognizes that a single context window is often insufficient for complex, multi-faceted tasks. Isolation involves splitting information across multiple distinct agents or execution environments to prevent cross-contamination (“Context Clash”) and manage complexity.

Multi-Agent Decomposition patterns

In a multi-agent system, a ‘Router’ or ‘Supervisor’ agent delegates tasks to specialized sub-agents. Each sub-agent operates within its own isolated context window.

Example of Multi-Agent Decomposition: The Research/Writer Pattern

Consider a task to research the history of AI and write a blog post. A single agent doing this would fill its context with disparate search results, making the writing phase prone to distraction. In an isolated architecture, a ‘Researcher Agent’ performs the search. Its context fills with raw data. It then produces a curated summary. This summary—and only this summary—is passed to the ‘Writer Agent.’

Thus, the Writer Agent has a clean context window containing only the relevant facts and the style instructions. It is isolated from the noise of the raw search data. This separation of concerns prevents ‘Context Distraction’ and ensures higher quality output.

The Supervisor and Sub-Agent Hierarchy

The ‘Lead Agent’ or Supervisor acts as the orchestrator. It maintains the high-level plan and delegates sub-tasks. Crucially, the sub-agents return only a condensed result to the Supervisor.

Context Partitioning:

This structure effectively partitions the global context into manageable shards. The Supervisor holds the “Global Context,” while each sub-agent holds a “Local Context.” This is akin to the organization of a software engineering team. The Engineering Manager knows the project status. Yet, the line-by-line code details are held in the local context of the individual developers.

This architecture allows for ‘Deep Agents’. These are systems that can go many layers deep into a problem without hitting token limits. Each layer operates in a fresh window.

Sandboxing and Environmental Isolation

Isolation also applies to the execution environment. When an agent writes code, it typically does so in a sandboxed environment (e.g., a Docker container).

Contextual Firewall:

The context engine acts as a firewall between the sandbox and the LLM. The LLM does not see the entire state of the operating system. It sees only the code it wrote. It also sees the standard output (stdout/stderr) returned by the execution tool.

This isolation prevents the model from being confused by environmental variables or system files that are irrelevant to the task. It also secures the host system from potentially malicious code generated by the model.

The Anatomy of Context: System, Knowledge, and Tools

The 4 types of context engineering describe the strategies applied to context. It is equally important to understand the structure of the data within the prompt payload. This is the ‘Anatomy of Context’:

System Context: The Constitution

The System Context is the foundational layer. It establishes who the model is (Persona) and how it should behave (Instructions).

- The Right Altitude: Anthropic advises that system prompts should be written at the ‘Right Altitude.’ Prompts should avoid vague high-level generalities. They should also steer clear of overly rigid, brittle logic. Prompts should focus on the outcome and the principles of the task, allowing the model to generalize.

- Immutable Constraints: This layer holds the “Deterministic Context”—rules that must be obeyed regardless of input (e.g., “Always answer in French,” “Never give medical advice”). These instructions are typically placed at the beginning of the prompt. This placement uses the primacy effect to make sure they are heavily weighted by the attention mechanism.

Knowledge Context: The Library

This layer provides the informational payload needed to answer the query.

- Static vs. Dynamic: It includes both static knowledge (brand guidelines, few-shot examples) and dynamic knowledge retrieved via RAG.20

- The Role of Examples: Few-shot examples are a critical part of this layer. Yet, instead of a random assortment, context engineering dictates the curation of canonical examples that show the desired reasoning process. These examples serve as a template for the model’s own generation.

Tool and State Context: The Workbench

This layer bridges the gap between thought and action.

- Tool Definitions: These are the schemas that describe what the agent can do. Effective context engineering involves optimizing these descriptions to be unambiguous and token-efficient. A vague tool description is a common cause of agent failure.

- Execution State: This tracks the results of earlier actions. If an agent calls a tool and receives an error, that error becomes part of the context.

- Session State: Variables tracking the progress of a multi-step task (e.g., “Step 3 of 5 completed”). This ensures the agent maintains continuity and does not repeat steps.

Standardization and Protocols: The Model Context Protocol (MCP)

As context engineering has matured, the need for standardization has grown. The Model Context Protocol (MCP) signifies a significant step toward formalizing the connection between AI models and their context sources.

The Three Primitives of MCP

MCP abstracts the complexity of integration into three primary primitives:

- Resources: These are passive data sources (files, database records, logs) that can be read by the model. They represent the ‘Knowledge Context.’

- Tools: These are executable functions (API calls, scripts) that allow the model to take action. They represent the ‘Tool Context.’

- Prompts: These are pre-defined templates that structure interactions, representing the ‘System Context.’

Decoupling Intelligence from Data

The significance of MCP is its ability to decouple the consumer of context, like the LLM or Agent. It separates them from the provider of context.

In a pre-MCP world, connecting an agent to a Google Drive required bespoke integration code.

With MCP, a ‘Google Drive MCP Server’ exposes resources in a standard format. Any MCP-compliant agent can essentially ‘plug in’ to this server and instantly gain access to those files as context. This changes context engineering from a bespoke coding task to a configuration task. It enables a modular ecosystem where agents can be rapidly composed. The agents have access to diverse datasets.

Failure Modes and Mitigation Strategies in Context Engineering

Despite best practices, context engineering is prone to specific failure modes. Understanding these is crucial for building robust systems.

Context Rot and Poisoning

Context Rot refers to the gradual degradation of model performance as the context window fills with noise.

Here, the model hallucinates or makes an error, and that error is recorded in the history. In following turns, the model “attends” to this error. It treats the error as a fact. This leads to a feedback loop of incorrect reasoning.

Mitigation: Strategies include strict ‘Context Pruning.’ This involves removing failed turns. Another strategy is ‘Verification Steps’ where a separate agent reviews the history for errors before proceeding.

Context Distraction and Confusion

Context Distraction occurs when the context is so large that the model loses track of the primary instruction. This is common in ‘needle in a haystack’ scenarios.

While Context Confusion occurs when the context holds conflicting information (e.g., two different retrieved documents contradicting each other).

Mitigation: ‘Isolation’ is the primary defense. By breaking the task into smaller scopes, the context window is kept clean. Additionally, ‘Constraint Setting’ (explicitly instructing the model to rank certain sources) can help resolve confusion.

I will be sharing a detailed blog post on the topic of failure modes in context engineering, subscribe to stay tuned:

Future Directions: Context as the Operating System

As we look to the future, Context Engineering is poised to become the Operating System’ of the AI era.

Just as an OS manages memory, processes, and I/O for a CPU, the Context Engine manages the information flow, state, and tool access for the LLM.

We are moving towards a world of ‘Context-Aware Computing’. Here, the context is not just text in a window, but a rich, multi-modal, and persistent state that follows the user across applications. Protocols like MCP will standardize how this context is exposed, and architectures like LangGraph will standardize how it is processed.

The role of the AI engineer is shifting. It is no longer about ‘whispering’ to the model; it is about architecting the stage on which the model performs.

The competitive advantage of the future will lie not in the underlying model, which is becoming a commodity. It relies in the proprietary architecture of the context engine. This means how effectively an organization can Write, Select, Compress, and Isolate its data to feed the cognitive engine.

Learn context engineering: more guides and next steps

Here are some next steps to ponder upon if you’re finished reading the guide till here!

Here are 8 actionable steps to apply context engineering, formatted for quick implementation:

- Audit Static Context: Review system prompts. Move large, static blocks, like long documentation or 50+ examples, into retrieval systems (RAG). This helps to reduce noise and cost.

- Implement a “Scratchpad”: Force your agent to keep a persistent state file (e.g.,

plan.mdortodo.txt) to externalize reasoning and prevent it from forgetting goals during long tasks. - Use Dynamic Tool Loading: Stop dumping every tool definition into the prompt. Use a lightweight classifier to “select” and inject only the tools relevant to the user’s current request.

- Set a Summarization Trigger: Automate “compression” by triggering a background summarization task when conversation history exceeds a specific token limit (e.g., 8k tokens).

- Isolate Complex Workflows: Refactor multi-step tasks into specialized sub-agents (e.g., one for Research, one for Coding) to make sure each operates with a clean, distraction-free context window.

- Optimize Prompt Prefixes: Keep the beginning of your prompt (instructions, persona) consistent across requests. This consistency maximizes KV-cache hits. It significantly reduces latency and cost.

- Adopt Model Context Protocol (MCP): Replace custom integrations with MCP servers. This change will standardize how your agents connect to data sources. These sources include Google Drive or Slack.

- Debug with Observability: Use tracing tools (like LangSmith) to inspect the exact context window during failures. You can’t fix ‘context rot’ if you can’t see it.

I will be adding more guides on various concepts in context engineering, learn with me here:

- Learn Context Engineering: Resource List (Lectures, Blogs, Tutorials)

- What is Context Engineering? – Learn Approaches by OpenAI, Anthropic, LangChain

Stay updated on our latest guides and tutorials we publish on using AI for practical applications:

This blog post is written using resources of Merrative. We are a publishing talent marketplace that helps you create publications and content libraries.

Get in touch if you would like to create a content library like ours. We specialize in the niche of Applied AI, Technology, Machine Learning, or Data Science.

Leave a Reply